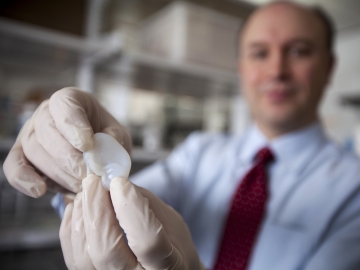

Dr. Bonassar displays a bioprinted ear. Courtesy of Lindsay France/Cornell University Photography.

Latest News

February 22, 2013

When William Shakespeare put the words, “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears” in the mouth of Mark Anthony, he may well have been prophesizing the future. Additive manufacturing (AM) has been a natural fit for prosthetic development and manufacturing, and now Cornell University and the Weill Cornell Medical College have taken prosthetics research to a whole new level with a bioprinted ear.

While every prosthesis is designed to be functional (and some to have artistic merit), they are artificial replacements for living material. Not so with the ear developed by Dr. Jason Spector and Dr. Lawrence J. Bonassar. The bioprinting process uses living material to create a structure that remains alive after being implanted and becomes another functional biological part of the human body.

“This is such a win-win for both medicine and basic science, demonstrating what we can achieve when we work together,” said Dr. Bonassar, associate professor and associate chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Cornell University.

The research performed by Spector and Bonassar is meant to combat microtia, “… a congenital deformity in which the external ear is not fully developed.” Around four children out of every 10,000 are born with the condition, which usually only effects a single ear. Many times, the inner ear is fully formed, but the outer ear is deformed or missing altogether.

The bioprinting process begins with a 3D scan of an intact ear, to generate a 3D printed mold. Researchers then add animal-derived collagen into the mold, and top it off with nearly 250 million cartilage cells. The collagen acts like a scaffold for the cartilage, directing its growth. Since cartilage doesn’t require a blood supply to survive, the process manages to bypass the need for vascularization, which has yet to be perfected with AM.

“The process is fast,” said Dr. Bonassar. “It takes half a day to design the mold, a day or so to print it, 30 minutes to inject the gel and we can remove the ear 15 minutes later. We trim the ear and then let it culture for several days in a nourishing cell culture medium before it is implanted.”

From there, the cartilage is given three months to fully grow, slowly replacing the collagen.

“Eventually the bioengineered ear contains only auricular cartilage, just like a real ear,” added Dr. Spector.

Once an ear has reached full development, it can be implanted into a patient. Spector and Bonassar say than the best time for implanting the new ear is when a patient is around five or six years old.

“We don’t know yet if the bioengineered ears would continue to grow to their full size, but I suspect they will,” said Dr. Spector. “Surgery to attach the new ear would be straightforward—the malformed ear would be removed and the bioengineered ear would be inserted under a flap of skin at the site.”

The research team intends to have fully developed the process in the next three years. If the project proves to be successful, it’s just the beginning of what could be possible for bioprinting.

Below you’ll find a video about the process.

Source: Weill Cornell Medical College

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

John NewmanJohn Newman is a Digital Engineering contributor who focuses on 3D printing. Contact him via [email protected] and read his posts on Rapid Ready Technology.

Follow DE